Artist Q & A - The Hidden Noise: Tinnitus and Art

With our exhibition, The Hidden Noise: Tinnitus and Art, a couple of weeks from opening, we interviewed the featured artists Nina Thomas and Fern Thomas about the art they have produced, their relationship to tinnitus and how it has influenced their art, and their experiences creating the art for this exhibition.

Q & A with the Nina Thomas

Nina Thomas – Work in Progress Image for OVADA (2021)

Could you tell us a little about the work you have made for the Tinnitus and the Arts exhibition?

My work for this exhibition explores the themes of loss and memory. In particular, I have been thinking about my own experience of tinnitus following a sudden hearing loss. I have often thought of tinnitus as a bodily response to loss. Tinnitus shares similarities with Charles Bonnet syndrome or ‘The Prisoner’s Cinema,’ in which a loss or deprivation is experienced, and the body response is to make that absence very, and often unsettlingly present. Tinnitus is a sort of haunting, but I think it’s also a memorial, creating something from an absence and turning into something else, something personal, intimate and responsive to who we are, our daily lives, our social selves and the impression our shared environments leave on us. Tinnitus is always a trace of our past selves and our environment. When I realised that tinnitus might be all these things, it changed my relationship to my tinnitus and to my hearing loss. My work for this exhibition is an attempt to reframe tinnitus this way – to represent tinnitus. It is a work of representation, and sort of a final act of mourning, representing a loss that is both part of me and separate; I have learnt to live with it, without feeling haunted by it.

Within this work I have returned to mediums I have previously used, such as projection/moving image and I have also been working with new materials. Some of these materials reference my past or attempt to make tinnitus an object or something elusive and intangible; each medium felt appropriate, for different reasons, in responding to the themes of this work. It has been great to work on this project and I am looking forward to sharing it.

How do you think the arts help in mediating, or expressing, experiences of tinnitus?

Experiences of tinnitus are so diverse, and the arts have always provided a space to think difference and imagine alternative realities, as well as identify with perspectives outside ourselves. It makes sense to create art about tinnitus as way to meditate on or express experiences of tinnitus. Also, the arts have historically been a space to make unseen and intangible experience present, and to create space for absence. I think the arts, therefore, are the perfect space to think through tinnitus.

Have you found that there is a part of tinnitus experience that you are particularly interested in?

As I say, for me, tinnitus is a sort of haunting of our past experience and interactions with our environments. I have always been interested in exploring experiences of loss in my work, but more recently I have been thinking about time and memory, and this has definitely come out of the research for this project. My experience of tinnitus is so personal, but it’s closely linked to who I am in the world, my interactions with others and how I spend my time.

I also associate my tinnitus with my deafness. I can’t separate the experiences out because I developed tinnitus suddenly when I lost my hearing. Throughout this project I have been particularly interested in tinnitus in relation to hearing loss and deafness.

Do you feel like it is important to have experienced tinnitus in order to make work about it?

It really depends on the nature of the work and the position you are taking. I don’t think we should only be able to make work about something we have personal experience of, but it is important to consider the implications of the work and ask questions of ourselves, about what we are doing, why we are doing it and our position in relation to the thing we are speaking about.

I experience tinnitus as an aspect of my experience as a deaf person. And, as a deaf person I feel strongly about what it means to speak on behalf of others, and the power relations that are potentially at play. This is because people speaking on behalf of deaf people has historically had devastating and long-lasting consequences on the lives of deaf people. Therefore, I do believe that representation by those with lived experience is so important, but it doesn’t mean I think someone without tinnitus couldn’t make work about it, however, one would have to be sensitive and consider all the implications.

When I was researching this project, I could not find many representations of tinnitus in the arts, examples of this seemed to be even more rare in the case of those living with tinnitus, so it would be great to see more work being produced on this topic. Also, tinnitus is so often thought of as tragic or maddening; I would love to see more representations which reposition tinnitus. I would also like to see more representation of tinnitus by deaf people. I do feel that there is something about the texture of the experience of living in a profoundly deaf body, experiencing tinnitus in the absence of almost all external sound that is so strange and beautiful. I like spending time without my cochlear implant, particularly in the morning, and when I am alone; I can feel much more present in that world; it reminds me of what it is to live in a body – one’s own interiority and bodily experience. The sound of my tinnitus is a part of that experience, the idea of the deaf body as silent is a myth, at least in my case. Living with tinnitus as a deaf person and what it means to me is something I still find it very hard to express in words; before I became deaf, I couldn’t have fully understood/imagined and represented that experience.

The exhibition uses very little audible sound. How do you feel about the relative lack of sound in the exhibition?

That there will be very little audible sound in this exhibition is fascinating. Much of my work is about trying to make present the loss of sound. I can see there could be some important and thought-provoking interpretations about what the absence of sound might mean.

On a more practical level, we were also very aware – when using sound – of our responsibility to other viewers who may have tinnitus.

Could you tell us a little about any roles that the concept of aural diversity may have played in the development of your work?

It’s difficult to speak about aural diversity without, again, mentioning my own personal experience. I was born with no hearing in my right ear, so I have never experienced sound from that ear, but I have also never experienced tinnitus from that side. I never experienced stereo sound, for example. Then, when I was in my early twenties, I experienced a sudden hearing loss in my other ear, and that was a massive change to my experience of the world. So, as someone who never had “normal” hearing, and who is now profoundly deaf and a cochlear implant user, I am always very aware of my own aural diversity. In addition, the various projects I have been involved in over the years, have often explored the diversity of our experience of sound, and so it is inescapable when I am making work that I think about it. I am still learning to hear with a cochlear implant. This has made me even more aware of how diverse our experiences of sound can be over the course of our lives, and how we all experience sound differently and in different ways at different times.

What do you think some of the difficulties are when making work about such a diverse and unpredictable thing as tinnitus?

I’ve read a lot about other people’s experience, and it has been fascinating to learn more about tinnitus and relate my experience to other people’s. I chose to create work from the position of my own lived experience because tinnitus is such a complex and difficult thing to speak about. When I was sharing early work with other people, in preparation for this exhibition, I found that others would begin to tell me about their experience of tinnitus. I like that art can function that way, as a space to share and hopefully it has some kind of healing or reparative function. I also realised how different every person’s experience is, and yet tinnitus is often represented in one particular way: as a high pitched continuous static sound. In my experience that isn’t the case. Tinnitus continuously responds to my life, my body and environment in surprising and unexpected ways.

Q & A with the Fern Thomas

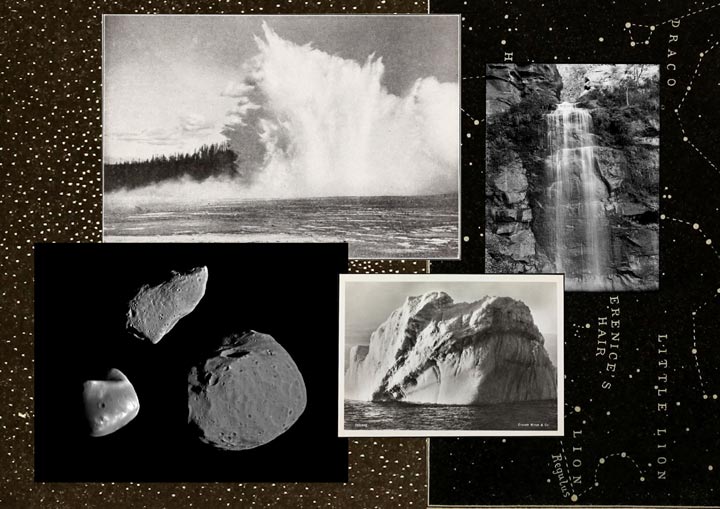

Fern Thomas – research image for ‘Sucking Sea Water Through Stones’ 2021

Could you tell us a little about the work you have made for the Tinnitus and the Arts exhibition?

The work has come from a set of growing questions that I have had and continue to have in response to my own experience of Tinnitus. I started to wonder (in a playful, imaginative way) whether what I was experiencing or hearing was actually the frequencies of the aurora borealis? That led me to think what would it be like if humans began to become attuned to the frequencies of natural phenomena or to the more-than-human world? That perhaps somehow what could be heard are the invisible voices of these elements and so the hearing becomes an invitation into a process of listening to and connecting with.

The work imagines different voices of future humans and their becoming receivers of nature’s frequencies such as volcano, glacier or aurora borealis.

Have you found that there is a part of tinnitus experience that you are particularly interested in?

Through my research and through this recent ‘being with’ my experience of Tinnitus I have unexpectedly found myself in the realm of ecological citizenship. If I believe that this inner sound could potentially be the frequency or voice of a volcano or of a glacier melting, what does that mean for my relationship or (a speculative future of) humanity’s relationship with the natural world? If we hear these voices, is it our duty to listen? It has allowed for a more expanded exploration of what tinnitus could be for me.

I think this exploration of the tinnitus experience has made me more attentive to the difference between hearing a sound and listening to a sound. That listening is a kind of gifting of attention.

Do you feel like it is important to have experienced tinnitus in order to make work about it?

I think this is a tricky one. I know I could only have made work that has come from my own experience of what tinnitus is for me.

The exhibition uses very little audible sound. How do you feel about the relative lack of sound in the exhibition?

I think it may seem that there is a lack of sound. I feel that for my contribution to the exhibition there is a calling on the ‘inner sound’. I suppose the words offered in my work invite a conjuring of sound which the person experiencing the work can have more control over?

Could you tell us a little about any roles that the concept of auraldiversity may have played in the development of your work?

When sharing personal experiences or reflections as part of my work, it is natural for me to work with spoken word and sound, pretty much always as a first person narrative. This exhibition has challenged me to think of different forms that is hopefully more sensitive to auraldiversity. It has also enabled me to think in different voices, developing texts connected to the different natural phenomena.

What do you think some of the difficulties are when making work about such a diverse and unpredictable thing as tinnitus?

Due to the diverse nature of tinnitus it can be daunting to think that the work needs to reflect the multitudinous ways tinnitus can manifest and be experienced, there is an urge to acknowledge all of the forms and all of the personal experiences. It turns out this is not possible. For my process of making the work I found I could only respond to how I experience tinnitus while holding the sense that this is not the only way. I think I developed the idea of different voices talking about their inner sounds in my work as a way of beginning to navigate voices other than my own when I had originally planned to have one person’s narrative documenting the movement through a landscape of different sounds.